Are we witnessing the Fall of the U.S Empire?

In what follows, the macro level conflict formation of US Empire will be reflected through my personal experience: Based on details from my work in Lawrence (Kansas/USA) during the successful period of the Sanders campaign as well as conversations and debates from this time, it’s safe to say that it has never been more exhausting to be a citizen of the United States’ Empire. Johan Galtung’s theoretical insights into culture and conflict dynamics have helped me make sense of the presidential election process unfolding since August 2015. This peace and conflict studies approach to understanding the role of culture and conflict in the election process can help elucidate important implications of both candidates’ stances.

While completing studies in Argentina and Chile in 2015, I explored US cultural imperialism in Latin America in cooperation with the Galtung-Institute for Peace Theory and Peace Practice. Insights from this work, particularly my work on Project Camelot, prompted me to engage my peers in examining the impacts of US deep culture on the maintenance of its empire and, by extension, its significance and relevance for the frustrating developments of the unfolding 2016 election process.

As it stands, the electoral process has presented the American people with Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump; two presidential candidates that hold the lowest favorability ratings in modern history. Political alternatives were easily subjugated before the official party nominations. The concession of the Democratic primary race by Bernie Sanders to Hilary Clinton on July 12th, two weeks before the Democratic Convention, depleted the broad-based movement that desired to address underlying structural faultlines in the United States. This concession was crucial, because from a geopolitical perspective, the Sanders campaign represented the choice towards more positive peace as set forth by Prof. Johan Galtung in his book “Fall of the US Empire: And Then What?”, namely “to integrate with the rest of the world as equals and solve the underlying contradictions of empire”. More specifically, Johan Galtung’s predictive approach to the study of Empire posits that empires fall due to synergizing contradictions in their political, economic, military, and cultural dimensions of power. The challenge for the next president will then be to solve these contradictions; or else…

Understanding Culture

The political conflict at the heart of the US presidential election is a reflection of a deeper, a cultural conflict over both the identity of individual Americans and the identity of the United States and its role in the world at-large. Resolving this conflict over cultural identity is more difficult due to differing perspectives of what constitutes culture. Culture is defined as, “The ways in which individuals and groups make meaning of their social and physical world, and the values, beliefs and processes that are reproduced through this meaning-making.” Culture can be a conscious process of meaning-making (surface culture) or an unconscious process whereby a person acts out a cultural script (deep culture). The iceberg model of culture delineates three levels of culture- surface, shallow, and deep. Surface culture includes food, dress, music, arts and other elements that could be easily identified as ‘culture’ by an outside party. However, the majority of culture lies in the unspoken rules and deep-seated rules below the visible surface culture. As cultural norms become deeper and more unconscious, the emotional attachment becomes greater and therefore more difficult to alter. The US presidential elections provide a perfect example of how deep culture limits legitimate dialogue over cultural elements that lead to conflicts. The entire spectacle of the 2016 election cycle includes celebrations, ritual, clothing, and art that are surface manifestation of this deep cultural understanding. Examining the elections from a cultural perspective helps “challenge the universal claims of much mainstream international relations and political and social science.” Peace and Conflict studies experts like Rubinstein and Foster as well as Avruch and Black at George Mason University also insist on the cultural approach to reading politics because ways of handling conflicts in general and of the US in particular are not actually universal. Rather, they are based on a particular history, geography, and anthropology deeply rooted in Western civilization.

Understanding US Deep Culture in the 2016 elections

US deep culture is fundamentally derived from Judeo-Christian theology. This religious cosmology is the foundation for the ‘civilizational code’ that provides the subconscious script for behavior in situations of crisis and conflict. This script is especially strong, as its roots can be traced back to ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia and East Asia. The historical context is important because small Christian tribes relied on the strength of a powerful God to survive and compete with other social groups. Christianity can be characterized as a singularist and universalist religion. Singularist in that it stipulates one God that rules the Universe, particularly in favor of a specific set of Chosen People.

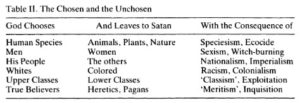

The concept of one God delineates a fundamental cultural distinction between Self and Other. This theological tenet further develops into six cultural concepts that are particularly violence-prone: 1-Dualism, 2-Manichaeism, 3-Armageddon (DMA) and 4-Choseness, 5-Glory, and 6-Trauma (CGT). Dualism is the understanding according to which the universe is fundamentally divided into two parts. Manichaeism, an attitudinal stance named after a theology developed by the Iranian prophet Mani, denotes this dualism as forces of Good and Evil eternally struggling for supremacy. Armageddon is the idea that a total, zero sum ‘final battle’ between Good and Evil will settle the eternal struggle. These elements help operationalize CGT. In the context of the United States, Choseness is the belief that the United States is a chosen nation, a “city on a hill,” a beacon of the democracy for the rest of the world. With the theological backing of the all-powerful God, the United States has been chosen to enact the divine mandate on Earth. Galtung further clarifies, “The smallest people with the biggest God and a clear mission in the world if and only if they keep their side of the pact. In other words, a linkage between moral behavior as defined in a religious context and foreign relations, relations to other peoples. Fulfilling the commandments becomes not only an individual obligation and a condition for one’s own salvation, but a collective obligation to be fu1filled by everybody for collective survival. Internal religious control becomes a social necessity.” Below is a table outlining the consequences of the theological divide between God’s Chosen and what is “left to Satan:”

(Click to enlarge)

Equally important are the notions of Glory and Trauma which refer to important historical points in time, events, or periods in a culture’s cosmology. During the Presidential election, these glory and trauma points are referenced frequently. For instance, September 11, 2001 is a Trauma point that is often used to legitimize military expenditure and wars abroad. In the rhetoric of both candidates, to remedy and recover from this trauma, the glory of American Exceptionalism and it’s hegemony in the international community must be maintained. These concepts are cemented firmly in Donald Trump’s slogan- “Make America Great Again” or in Hilary Clinton’s recent statement “part of what makes America an exceptional nation (…) is that we are also an indispensable nation; in fact; we are THE indispensable nation.” Trauma is a threat to the collective psychology of a people, or the ‘collective subconscious’ in Jungian terms. Trump’s framing in particular seeks to remedy trauma and other U.S handicaps through the restoration of self-referential Glory. Indeed, watching the presidential election unfold in the context of the U.S Empire reveals cultural patterns embedded in structures which are silent, do not show – are essentially static, like “tranquil waters.”

In many ways, the Sanders campaign sought to provide an alternative to the DMA, CGT way of thinking by focusing on underlying economic, social, and political issues, absurdities and contradictions inherent in the US imperial structure. For example, Sanders wanted to challenge wealth inequality by reforming the tax system, increasing the minimum wage, and empowering the “99%.” Sanders’ economic platform was bolstered by his refusal to take corporate money for his campaign. For many people in my hometown Lawrence, – [and here, geography matters because Lawrence is considered a “dot of blue in a sea of red.” The town is “more liberal” (to quote a prominent misclassification and political misunderstanding in American politics) than the rest of Kansas.] – Sanders represented a break from ‘politics as usual’ and a credible step toward the construction of a peace culture. He acknowledged a need for the creation of a more equitable society. On March 3rd 2016 at a Sanders rally at the Douglas County Fairgrounds, people lined up around the block and waited several hours to enter the arena. During his speech, he focused on challenging corporate control of US politics, strengthening minority groups in the political realm, and ending US military intervention abroad. In this manner, the rhetoric of Sanders portrayed a more inclusive US Self. The “we” usually referenced in the media refers to the identity of the liberal nation-state and the elites rather than its subjects. In Sanders’ approach however, the central tenet of a peace culture stood out: He sought “unity in diversity” by fully taking into consideration the infinite wealth of the cultures of the world and by averting the ‘fear reflex’ when confronted with otherness.” Additionally, Sanders was more prone to utilizing the four aspects of peaceful communication as defined by de Matos in “Learning to Communicate Peacefully.” These include: Love your communicative neighbor, Dignify your daily dialogues, Prioritize Positivizers in your language use, and be a communicative Humanizer. A prime example is Sanders’ reaction to criticism from Native peoples that they were being excluded from the conversation. At said rally, I witnessed a student from Haskell Indian Nations University introduce Sanders, who then dedicated a significant portion of his speech toward highlighting indigenous rights, tribal sovereignty and the effects of wealth inequality on native populations. Lester Randall, Chairman of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas and my colleague through my position at Kansas University, sat on the stage during the rally as well. Sanders’ stump speech evolved through dialogue with the electorate, an act of cooperative narrative construction that granted respect and dignity to voices that were normally marginalized. This positive approach outlined a vision for an inclusive and peaceful future.

In contrast, Clinton’s approach remains more negative and fear based. It focuses on “defeating the Republicans.” The DMA script was routinely invoked by the Clinton campaign including during the Democratic primary to defeat the challenge of Bernie Sanders. As the corporate candidate, Clinton was unable to counter the political and economic arguments of Sanders. Instead, she exploited the dualism of the two party system. During the democratic debates she would routinely sideline the substantive comments of Sanders by reinforcing the manichaeist idea that the ‘Good’ Democratic Party needed to unite and defeat the forces of ‘Evil’ represented by Donald Trump and the Republican Party. Considering ideas outside of the prominent Liberal discourse, or entertaining the politics of Bernie Sanders, was rejected because such a split of the side of good would result in defeat in Armageddon (read: election day). In turn, she relied on tropes of American strength and the fear of the state losing legitimacy if Trump were to be elected.

In a sense, deep culture is one of the primary reasons for the autism of the US Empire and its inability to understand the goals, needs, and interests of the world at large. The surface culture in the United States reflects the underlying cultural understanding of conflict. Seen in this way, DMA/CGT in the United States is an obstacle for peace and peace culture. Attempts to alter this mindset are sidelined in public discourse, because “realpolitik approaches” have marginalized cultural approaches.

Remembering the BERN

In a speech for UNESCO, David Adams explicitly draws the connection between peace culture and empire. Adams outlines two symptoms- economic and political- of the culture of war and empire. Economically, the state encounters a balance of payments problem because the states puts money into the military, but doesn’t appropriately develop industry or exports. Politically, there is political alienation because the people no longer believe that the government works with them. People in my generation have lived almost the entirety of their adult lives under the War on Terror – Sanders tapped into this latent desire to move towards more peaceful status quo. The historical trauma of 9/11 has been utilized to justify governmental expenditure on war rather than health care, education, or the social safety net at large. This system is a form of violence, as “human beings are being influenced so that their actual somatic and mental realizations are below their potential realizations.” Indeed, Sanders’ volunteers like myself, framed our commitment to the Sanders campaign directly in these terms. Millennials are still searching for political answers to student debt, and rather than providing an answer, the presidential elections have only cast more doubt. I heard many stories about how student debt was destroying the future of this generation. The campaign was an opportunity to develop a culture of peace that challenge the deep culture of empire and put people back at the forefront of politics. Volunteers were enthusiastic, because they felt like their voices were being heard, and that the collective project of “Feeling the Bern” challenged the violence of the current system.

What about Violence?

Galtung’s violence triangle helps conceptualize the different prongs of the Sanders campaign. The three types of violence- direct, structural, and cultural- were experienced by campaign staffers to different degrees depending on their socio-economic status, race, gender, and age. For example, many white, lower-middle class staffers were interested in the structural violence of student debt and the underlying economic structures that increased suffering through lack of employment and low wages. Many staffers of color were concerned primarily with ending police brutality- both the dimensions of direct, individual violence of police murder and the structural components of the prison-industrial complex and The New Jim Crow. As mentioned above, the campaign’s platform as a whole challenged cultural violence through inclusivity and criticism of mainstream and liberal political thought.

The campaign also made a distinction between direct and indirect violence that was important to hold individuals accountable for crisis and war without losing legitimacy through ad-hominem attacks. For example, the members of the military and specific politicians were subject to criticism, but the analysis of violence was abstracted to the systemic level as a way to impulse policy change. This helped the campaign avoid the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness” whereby individuals are considered to directly responsible for structure, not acting within a system. This internal analysis of violence – even if the campaign didn’t necessarily express itself in these exact terms – resulted in a clear rhetorical superiority over the Clinton campaign. Sanders’ criticism was quite heavy on the political, economic, and military structures of misery in the United States. He was able to effectively link Clinton to those structures as a key player, but did not challenge her as an individual. For Sanders’ supporters, this distinction was a rhetorical device to avoid criticism that Sanders was attacking Clinton or mudslinging. In official events or the debates, Sanders was often asked if his criticism of systems and structures was directly addressing the actions of Clinton, and he consistently deflected such questions as ridiculous horse-race commentary perpetrated by the profit-driven media.

Clinton’s legitimization of war culture is directly related to her analysis of violence. As a devout realist, acolyte of Henry Kissinger, and Secretary of State, the foundation of Clinton’s rhetoric is security. Security is about diminishing threats. Thinking is limited to achieving a negative peace where the person, direct violence of other countries/groups does not occur. Of course, “focusing on reduction of personal violence at the expense of a tacit or open neglect of research on structural violence leads, very easily, to acceptance of ‘law and order’ societies.” Clinton reinforces the structures of American Empire by making the case that American’s are unsafe because the Others are not following the ‘correct’ international order. Violence and mass shootings in the United States that broke out due to structural conditions, in Clinton’s eyes, are due to individuals that are breaking the law suffer from mental disorder or personal psychosis. Or violence from structure is due to bad intentions and inherent Evil. This analysis failed to satisfy many Americans that have suffered structural violence, especially because Clinton’s vision of the future is limited to a vision of negative peace. A far-reaching vision of peace cannot be achieved without a foundational and equally far-reaching re-conceptualization of violence.

Many Americans are deeply frightened at the potential outcome of the election in November. Much of this fear stems from evidence that Trump or Clinton, the candidates that were ultimately selected, will be able to address the underlying structural formations that have caused so much suffering inside and outside the US.

The process has been disappointing for those who have an “unabated aspiration for peace, which implies the necessity of finding a way of living together better in this world of growing complexity and uncertainty that all too often is now witnessing the outbreak of new forms of violence.” Deep Culture has limited the spectrum of debate to Manichaeist ideas that deliver more violence, but little justice or understanding. My experience participating in the Sanders campaign and frequently discussing these issues explicitly showed me that people in the United States are keen to discover new ideas, not just reformist policy. Peace research can play a positive role in raising critical reflection about deeply held cultural elements by improving the understanding of violence and its causes, as well as the potential for positive peace in the form of an equitable and harmonious; empathy-literate society. Fortunately, culture is not static and can be changed. I am hopeful that as violence, in all its forms, continues to manifest with great frequency, Americans will consciously choose a culture of peace. If the US Empire and its structures deteriorate by 2020 as predicted by Galtung in 2000, the country will need to answer the question- “And then… What?” A timely answer would be “Peace Literacy.”

Keil Eggers – US representative of the Galtung-Institut to UPeace

Works Cited

Brigg, Morgan. “Culture: Challenges and Possibilities.” In Palgrave Advances in Peacebuilding, 329–46. Springer, 2010.

De Matos, F.G. “Learning to Communicate Peacefully.” In Encyclopedia of Peace Education, edited by Monisha Bajaj. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University: IAP, 2008. http://www.tc.columbia.edu/centers/epe/entries.html.

Eggers, Keil. “AND THEN WHAT?” And Then What? Zine. Accessed September 13, 2016.

Galtung, Johan. “A Structural Theory of Imperialism.” Journal of Peace Research, 1971, 81–117.

———. A Theory of Civilization: Overcoming Cultural Violence. Transcend University Press 9. Oslo: Kolofon Press, 2014.

———. “Cultural Violence.” In Violence and Its Alternatives: An Interdisciplinary Reader, 1st ed., 39–53. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

———. The Fall of the US Empire – And Then What? TRANSCEND University Press, 2009.

———. “TRANSCEND MEDIA SERVICE » Who Runs The World? The Subconscious(*).” TRANSCEND Media Service, December 30, 2013.

———. United States Foreign Policy: As Manifest Theology. University of California, Institute on Global Conflict & Cooperation, 1987.

———. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (January 1, 1969): 167–91. doi:10.2307/422690.

lyonstreet1. Culture of Peace Pt. 5. Global Movement to Replace the Empire. International Leadership Development Program Conference of the University of Connecticut Institute of Comparative Human Rights, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWfkQLe0B6I.

Preis, B, and C.S. Mustea. “Background Note: The Role of Culture in Peace and Reconciliation.” Paris: UNESCO, 2013.

Stang, Hakong. “The Centre- Periphery Myth of the World: The Origin of Universalism in Eurasia.” Trends in Western Civilization Project. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo, n.d. https://www.transcend.org/files/?id=551ebebf08338.

Thapa, Manish. “Session 6: Culture, Conflicts and Peacebuilding.” Lecture presented at the UPM 6001 UPEACE Foundation Course, UN Mandated University for Peace, August 29, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnNLdjmrsCs.

![[X]](/img/dialog-close.png)